Assessing Russian Casualties

Part II: Drafting an Initial Russian Order of Battle on 24 February

In the process of refining casualty estimates, I created a working order of battle for Russia on the Ukrainian border as of 24 February. I did have to simplify things somewhat given time constraints. In addition to the casualty estimates, I anticipate these being useful for wargaming endeavors in the future and I will continue making adjustments in the coming months. Similar to Part I, this is almost as much for me as anyone else as writing this up encourages me to document my processes thus far.

Obligatory declaimer: Nothing here should be regarded as definitive yet and is still a work in progress. This is likely also to be very dry reading for many, while exciting for a few. BLUF/TLDR: Assuming roughly 70% of expected prewar manning, 120 Russian conventional and VDV BTG’s of variable strength on 24 February, 72k personnel within these BTG’s, 12k-24k at division/brigade/regimental level outside of task organized BTG’s, at least 10k special forces, 30k-40k in support units, at least 10k initially deployed with the National Guard. 134,000 to 156,000 total, not including the Russian Air Force and Russian backed separatist forces. Totals for Russian forces fighting northwest of Kyiv: 20,900 to 27,700, trending toward the smaller figure. The Russian back separatists in 1st and 2nd Army Corps likely numbered approximately 25,000 pre-24 February, with many units below 50% strength.

Counting up Battalion Tactical Groups

For the initial phases of the war, Russian forces were counted up mainly using Battalion Tactical Groups (BTG’s). There are a few western oriented sources it stands for Russia’s force posture on the eve of 24 February. The first are the official statements, mainly from unnamed United States’ defense officials, in the leadup to the invasion. The early February number was approximately 110 Battalion BTG’s and 142,000 personnel that was widely cited by the media and various think tanks.1 This later increased to 120 BTG’s and 150,000 to 200,000 personnel.2 Already, we run into a issues when it comes to these numbers. Does this include the Russian-back separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts of 1st and 2nd Army Corps? Probably not as those forces were there prior to the buildup. Does it include the Russian National Guard, which deployed several units in the early days of the invasion? Possibly, but seems a bit unlikely.

And of course, the defense officials statements avoid giving details on which units were deployed where. Konrad Muzyka tracked the deployments with his consulting group in the months prior and was able to determine the approximate locations of 98 of the BTG’s on 20 February, the summary of a which is here. I was able to track deployments to a small extent starting in January and, in every case, what I found closely mirrored what Konrad had already developed.

Now we come to the more ontological problem: how big was a typical Russian BTG on 24 February? Some have done the basic calculations based off what the officials gave us in the lead up: 142,000 / 110 = 1,290.9 or 200,000 / 120 = 1,666.7. Both of these are obviously too big, so the official estimate includes at least some number of supporting troops that are not within BTG’s.

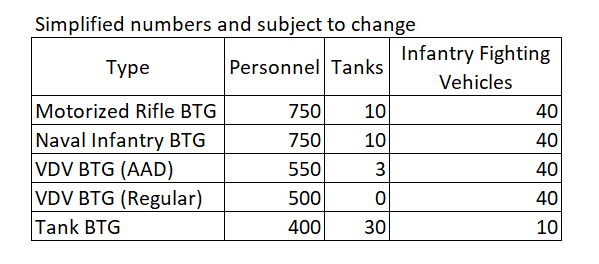

Our prewar understanding of BTG manning would suggest a typical motorized rifle BTG would have been about 900 personnel. Clarifying the initial western estimate means 900 x 120 = 108,000 personnel within the BTG’s. Assuming 200,000 total this means 92,000 supporting personnel outside of the BTG’s, if the total number was 150,000 this would go down to 42,000 supporting personnel. We can further refine this number. We know the number within a BTG varies on the base unit used. A VDV or tank battalion based BTG will have less personnel that a motorized rifle BTG. We also know that, in general, BTG’s were somewhat smaller than expected, due to a combination of using mainly contract personnel (barring a few notable examples) and a possible organizational change reducing the authorized strength of motorized rifle battalions. Combining what Konrad did with some of my own research yields this BTG breakdown:

Once you add up the totals, you get 122 BTGs, quite close to the final western prewar estimate. Some of the geographical areas and forces overlap. For instance, 90th Guards Tank Division initially came in from the Chernihiv direction and unsuccessfully approached Kyiv from the Brovary area. The 47th Guards Tank Division appeared briefly in Sumy, then Kharkiv, then Izium. I also divided up the forces into two columns, an initial force set and a follow on set of reinforcements. Going back to the first days of the war, it is evident there was some echeloning of the Russian forces. This was probably due to a combination of factors, including terrain restrictions around Kyiv and Crimea, forces still being in the process of deploying to the Ukrainian border, and some forces likely being held back to exploit any success. During the evening of 24 February, the Ukrainians believed about 60 BTGs (about half of the initial force) were on Ukrainian territory.

By 3 March, only about six were not in Ukraine yet according to the Ukrainian General Staff.3 I also think there is a possibility many of these may have been on Ukrainian territory at this point, but not heavily engaged prior to the second week of the war. In some cases, these follow on reinforcements may not have been used at all until the mass withdrawal of forces from Kyiv, Sumy, and Chernihiv Oblasts. These numbers do not include the supporting units, the Russian back separatists, or National Guard. More on those in a bit.

Tank and Infantry Fighting Vehicle Estimates

I also want to start exploring the relationship between armored vehicle and personnel losses, using both the Oryx data and the Ukrainian General Staff estimates. As previously stated, I believe the Ukrainian General Staff estimates may be inflated to some extent (like almost all wartime estimates of enemy casualties), but the broader patterns in their numbers appear to correlate to what we have been able to verify independently. The 120,000 “liquidated” figure that is regarded as KIA by many I think applies to both killed and wounded.

The General Staff figures for tanks losses are pretty self explanatory. However, the General Staff also uses the term “бойових броньованих машин” which they translate to English as “armored personnel vehicles” on their press releases. “Armored combat vehicles” would probably be slightly more accurate (бойових means combat). Armored combat vehicles should include BMP’s (Infantry Fighting Vehicles) and BTR’s (mostly Armored Personnel Carriers, but the BTR-82A could be argued to be an Infantry Fighting Vehicle by some due to its armament). There are also a wide variety of supporting armored vehicles that are neither IFV’s or APC’s. Recovery, engineer, and battery control vehicles for example.

Looking at the approximate 2 to 1 ratio of armored combat vehicle losses to tanks in the General Staff reports, it is not immediately clear if these are just IFV/BMP losses or include various APC/BTR/MTLB losses as well. Given that you would expect the most common BTG to have about 10 tanks and maybe 50 or more BMP, BTR, and MTLB variants (mainly the base motor rifle battalion, plus various supporting elements) one would expect the ratio to be higher. Accordingly, I will exclude vehicles outside of the maneuver battalions for now to keep the data consistent, which perhaps the Ukrainians hinted at by using the word “personnel” in their reports.

The rest of the vehicle types (artillery, air defense, sustainment, etc) I have excluded in the interests of time and the fact that the number of those vehicle will vary widely from BTG to BTG. I would thus offer these preliminary numbers as a baseline (these will almost certainly change later).

The VDV BTG are split into two subtypes as the 76th and 7th Guards Air Assault Divisions have tank battalions within their table of organization that the parachute divisions and air assault brigades do not. It seems reasonable that this battalion could be split up with approximately one platoon going to each BTG. The naval infantry brigades sometimes have a tank battalion but this is not universal either. Tank battalions can either have 30 or 40 tanks, for this exercise I went with the lower number for the tank BTG as that seems to be a little more common. The motorized rifle brigade BTG’s can vary depending of if it is based on a BTR or BMP battalion, BTR battalions having slightly more personnel; for this exercise I took the rough mean of the two. The Naval Infantry count may be off; they typically use BTRs or BMP-3s, in similar numbers to motorized rifle battalions as far as I know, but I do not have an exact table of organization for them at the moment. These simplified estimates assume BTG’s in most cases were about 60 to 80 percent strength in terms of personnel when compared to prewar expectations.

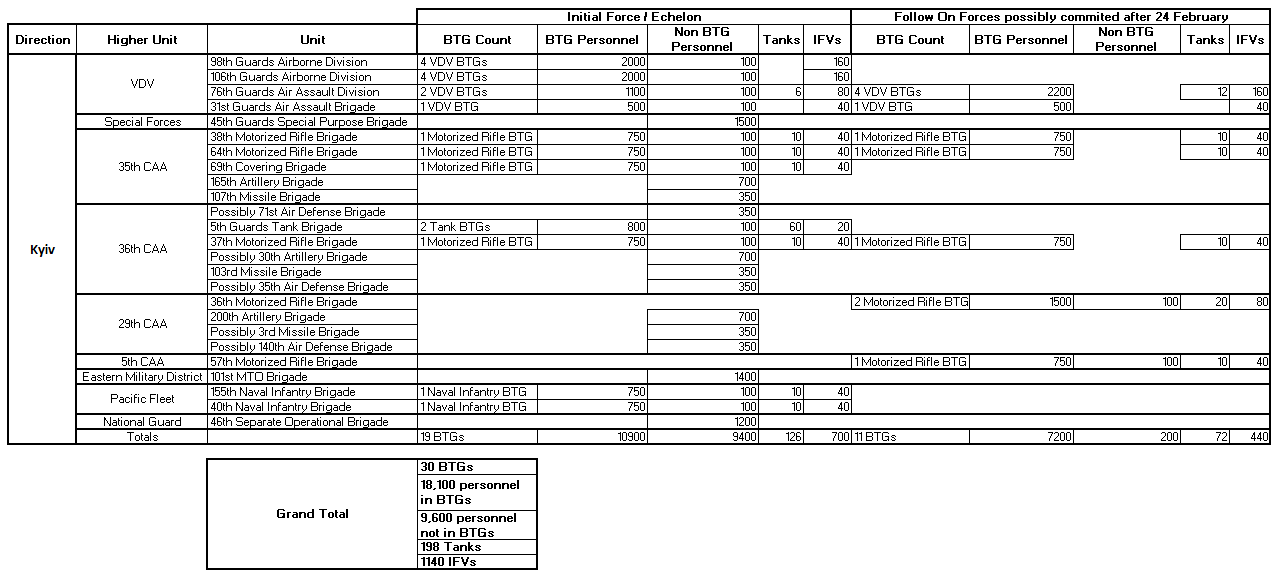

Now we can combine this with the previous BTG breakdown by geographical area.

Compare this to the previous estimate based on 120 BTGs of about 900 each being 108,000 BTG personnel. The above table’s 72,200 number is in line with the previous hypothesis of BTG’s overall being anywhere between 60 to 80 of expected manning. We should try to account for various special operations forces and recon brigades which are not as trackable as conventional units. The 45th Guards Special Purpose Brigade being an example of this. Assuming roughly one GRU/SOF brigade per geographical area adds another 10,500 personnel total. The tank numbers are similar to a prewar Ukrainian estimate of 1,200 tanks deployed initially. The IFV count is high in comparison to a prewar Ukrainian estimate of armored fighting vehicles of about 2,900. It’s possible their number only included BMPs, and not any sort of BMD or BTR variant. I might try adjusting to try to compensate for that in the future.

Support Personnel

As far as revising the supporting personnel count, previously stated as 42,000 to 92,000, there are a number of ways forward. Generally, each combined arms army has an artillery, air defense, and Iskander brigade, plus a engineer regiment while each military district usually has a MTO Brigade and MLRS Brigade. This assumption would yield about 11 artillery, air defense, Iskander brigades and engineer regiments each at the CAA level and 4 MTO brigades, and 4 MLRS brigades at the district level. These numbers are likely high as the limited reporting we do have indicates much of this was not in place by 24 February.

This gives us about 41,000 support personnel at full strength, quite close to the lower bound of western estimates for non BTG personnel. If manning was similar to the BTGs (70%), this total would be 28,700 instead. The various formations that deployed BTGs also probably had elements that were not task organized with the BTGs themselves (likely a couple hundred each, so 12 to 24,000), possibly accounting for most of the remaining difference in support personnel. These 12,000 to 24,000 troops would have been brigade or regiment reporting forces like the headquarters staff and elements of MTO battalions and companies. The western estimates also probably included air force personnel, who’s total may have been another few thousand.

National Guard Forces

The Russian National Guard (ВНГ) does not get much attention in western sources but represents a possible manpower pool that could be utilized in special operations, light conventional combat, and counterinsurgency roles. A number of National Guard units took part in the initial invasion. The most well known of these is probably the 141st Special Motorized Rifle Regiment, the “Kadyrovites” from Chechnya. They are officially a part of the 46th Separate Operational Brigade of the National Guard, which probably had at least 1,200 personnel involved in the attack on Kyiv. The National Guard also has many Special Purpose Detachments, usually having between 150 to 200 personnel each. One of these mistaken drove into the suburbs of Kharkiv in the beginning of the war and was ambushed. More research is needed in this area, but for now, I am assuming roughly 10,000 were involved in the initial invasion. Russia has 11 Separate Operational Brigades and many detachments. At this point in the war (January 2023), more may have been pressed into frontline roles they are not ideally suited for.

Refinements to the Western Kyiv Order of Battle

Here is the February 2022 Russian OB as it currently stands for Kyiv. This is for troops on the west side of the Dnipro only.

The final total of 27,700 personnel falls within the range of the 20 to 30 Russian thousand troop estimate I have seen for Kyiv. I have left off engineering regiments because I have no reporting of them being involved, but they could have been there. There may also be missing SOF and National Guards forces. 29th and 5th CAA were not fully deployed by 24 February. The missile brigades stayed within Belarus. The total engaged number probably falls closer to the 20,300 total from the initial echelon as we know the Russians had significant difficultly in deploying their forces due to terrain restrictions and effective Ukrainian resistance. The terrain is the same and the VDV is significantly depleted, making any future significant advance against Kyiv from this direction unlikely.

Russian Backed Separatist Forces

The 1st Army Corps had five motorized rifle brigades, three regiments, and about a dozen separate battalions. Information from 2020 indicates these units were at approximately 50% strength in manpower. 4 The equipment situation was supposedly better, around 80%. This information is quite old but it matches more recent things I have heard. The 2nd Army Corps is described as more effective and better manned. It is smaller at three motorized rifle brigades, two regiments, and about ten separate battalions. Each corps also has an artillery brigade.

A separatist motorized brigade's paper strength is about 3,000 personnel each and is authorized 30 tanks (mostly captured T-64's) and approximately 100 BTRs or BMPs. The separatist brigade’s organization is largely similar to a conventional Russian unit. Territorial defense battalions are attached to make up manning shortfalls in some cases. Overall, the separatists offensive potential was limited, although the 2nd Army Corps did have some success in the Severnodonetsk area until Ukraine moved in reinforcements.

Totaling up the separatists forces for 24 February in general is difficult and they have since mobilized. Rob Lee stated 15,000 to 25,000. I would say it was probably on the higher end. Assuming the motorized brigades had 1,500 personnel each at the start of the war, the brigades alone made up 12,000 total.

Moving forward: A more sophisticated unit and order battle database

The methods used above are taking a number of shortcuts due to time limitations. Eventually, I want to take this a make a much more sophisticated database of units and equipment, possibly including other nations besides Russia. Here is an type lookup table built out in Access, though eventually I’ll move this to an SQL format probably.

This table feeds into a number of different things, here is a table for the 38th Motorized Rifle Brigade.

Using the type lookup table, you can then set up queries to derive fuel and ammunition figures at the brigade level.

Obviously I am very early on in this process but the end goal is to have the best open source equipment database available.

Seth G. Jones, “Russia’s Ill-Fated Invasion of Ukraine: Lessons in Modern Warfare,” CSIS, 1 June, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russias-ill-fated-invasion-ukraine-lessons-modern-warfare.

“Russia’s War in Ukraine: Military and Intelligence Aspects,” Congressional Research Service, 14 September, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47068.

Ukrainian General Staff Update, 3 March, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/264138929232526.

“Intelligence data on 1st and 2nd Army Corps of Russian Federation in occupied Donbas,” 8 September, 2020. https://informnapalm.org/en/intelligence-data-on-1st-and-2nd-army-corps-of-russian-federation-in-occupied-donbas/.

Dear Henry, not sure if someone has pointed this out before. You might want to check the copy-editing of the headline of your whole Substack..

Totally off topic. My FIL was Army CIC, late husband also retired AF officer. I have been concerned for quite some time about Gen. Austin. My understanding of the civilian-military relationship would never see a military person as Sec Def, just as we would never see a civilian as one of the Joint Chiefs, because a military officer *never* is to be put in a position to outrank the highest civilians. Can you give me some references to explore the dynamics between these positions in wartime, that we seem to be heading towards? I feel it was done for a specific reason, that has been buried or glossed over.